Know Your Limits: How Pesticides Protect Your Food Supply

By Dilia Narduzzi

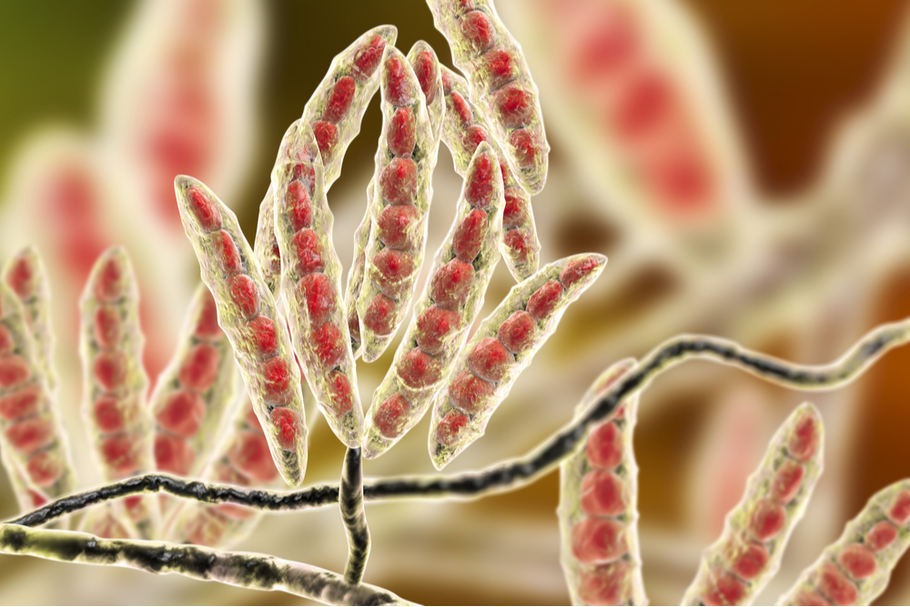

Before a new pesticide is brought to market, it undergoes rigorous testing to make sure that handling it is safe for farmers and any residue left on the plant is within certain allowable limits, i.e. safe for human consumption. In June of 2021, a new fungicide, picarbutrazox, used on canola and corn crops, had what’s called its maximum residue limit (MRL) imposed by Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA). All pesticides used on crops must go through this testing process. While each country sets its own MRL, they are coordinated worldwide.

Prices for fruit and vegetables would be 45% more if “pesticides weren’t used to increase crop yields.”

But how does the system work? The key aim is to “minimize human exposure. The rule of thumb is to use as much as you need to achieve the end product, which is to kill the bug that’s jumping around on your lettuce, but use no more than that,” says Dr. Leonard Ritter, a professor in the School of Environmental Sciences at the University of Guelph and an expert in pesticides and their safety protocols. Before any farmer can use the product, the company manufacturing it must go through trials. Results of the trails are submitted to organizations like Health Canada’s PMRA and they’ll either decide the “chemical can be used safely at the concentration that’s being proposed or it will be rejected. We’re not going to approve chemicals that cause cancer or are inherently explicitly toxic,” says Dr. Ritter.

What’s more, maximum residue limits are set for each chemical. “This limit is the maximum residue expected to be on a crop if the product is used according to the label directions, at the highest possible rates and the highest possible frequency,” says Pierre Petelle, President and CEO of CropLife Canada, an organization dedicated to the interests of the agriculture industry in Canada. And even though the name, “maximum residue limit,” seems to indicate human health and safety, the MRL has more to do with international trade standards than human health. What health regulators then do is take the MRL and “determine what an acceptable daily intake level would be for that product,” says Petelle. The regulators act conservatively. For example, if someone eats three bananas a day for the rest of their life, what would be an acceptable level of the pesticides used on bananas for that person over their lifetime, creating no negative impact on their health? “The difference between that number and the MRL is at least a hundred and sometimes even a thousand times lower” than what’s considered safe for human consumption, says Petelle, meaning there’s a huge safety margin factored in.

In some cases, an MRL can change, or can have a proposed change, as has been the case recently in Canada with glyphosate, the predominant chemical in Roundup. There was an application to increase the MRL of this and a few other chemicals, but the Canadian government put a halt on those proceedings for the time being. According to an August 2021 press release from Health Canada, “no increases to MRLs” will happen “until at least spring 2022,” citing the desire for “transparency and sustainability” for Canadians. MRLs can change for a variety of reasons, sometimes to align with international standards, says Petelle. Another reason is for efficiency. Crops can be grouped together. For example, blueberries have recently been grouped with all other berries. In so doing, the MRL was raised to accommodate the new grouping. This doesn’t mean that blueberries will be sprayed more or grown differently, it means the entire group of berry crops has a different MRL.

This system ensures food safety as well as an “abundant, wholesome food supply, at prices that are incredibly cheap,” says Dr. Ritter. Many of us balk at our grocery bills, but according to CropLife Canada, prices for fruit and vegetables would be 45% more if “pesticides weren’t used to increase crop yields.” CropLife Canada has a startling graphic that puts pesticide use and human health into perspective. A man would have to eat over 25,000 carrots in a day and to experience any negative health effects from the pesticides used on carrots, a woman over 18,000. Dr. Ritter says Canadians can be reassured that “the primary priority is always human safety. There’s never any doubt about that. If we ever have any question about which way to go, we’re always going to go in favour of the human health outcome.”

About the Author:

Dilia Narduzzi is a freelance writer in Hamilton, ON. She’s written for Costco Connection Canada, Canadian Grocer, The Women’s Brain Health Initiative, Country Guide, Maclean’s, and other venues. She writes on health, food, agriculture, and books.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants