Managing Risk Will Ensure Food Safety Post-Pandemic

By Dr. Sylvain Charlebois

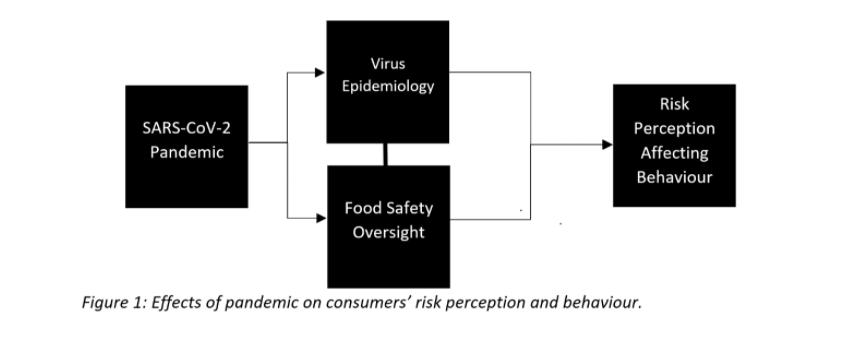

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a new era of food safety, in which risks are managed and perceived differently. This crisis has proven that food safety measures must be adjusted, even if the science related to the virus is ambiguous. Based on the science we had at the time of the outbreak, there was no evidence to suggest that consuming food was a risk or associated with COVID. The immediate impact of the pandemic on the food supply chain were, and continue to be, logistical. The food safety risks were implicit given how we thought the virus arose and how little we knew about it. Measures created by government authorities caused logistical disruptions which continue to be resolved.

As such, both industry and regulators alike need to broaden their scope of analysis when looking at food safety risks. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the already pressing need for closer collaboration between animal and human health researchers, conservation practitioners, public health, and environmental authorities. Without these collaborations, food safety assessments and measures cannot be as efficient or as comprehensive. Most critically, food safety policies often discriminate against small businesses, expecting them to deal with bureaucracy in the same way as large companies. This typically results in increasing exposure to supply chain disruptions and rates of shutdowns. When new food safety measures are implemented, small and medium sized businesses are often left behind. Interventions are also overblown, and smaller companies can’t handle regulators’ demands. Canada’s listeria crisis is a good example. How smaller businesses are supported when new risks emerge will be critical for the sustainability of the agri-food sector.

The future of the food industry will likely be permanently changed post-pandemic. In most parts of the world, the industry is labour-intensive and most operations are not capitalized enough to allow for automation and the use of robotics. Risk management within food facilities will change. Food systems will be restructured, and greater priority will go to controlled environments in farming, processing and distribution, reducing the dependency on labour across supply chains.

Bioanalytical tools such as effect-based analytics, immunoassays, and immunosensors will better anticipate risks in the future. Stakeholders, from farm to fork, will need access to these technologies to detect toxins and allergens in their food ingredients and products.

The power of data science and analytics has been illustrated throughout this pandemic. Open and predictable markets integrating more data science is critical to smooth the distribution of food along supply chains, as well as ensuring food moves to where it is needed. Analytical platforms can combine data on temperature, humidity, and duration in the food chain to forecast pathogen infection and act before a contamination occurs.

Post-lockdown public health officials should use more data science in their surveillance of the situation, as well as depend more on the development of appropriate bioanalytical tools. This tactic will be beneficial with regards to both the screening of populations and the monitoring of food, surfaces, and surrounding environments. Technologies can be developed to support industry in its effort to make food supply chains work efficiently.

We will likely face more pandemics in the future. Unless fundamental changes are made to anticipate zoonotic diseases, much of the global response to these outbreaks will continue to be reactionary. The focus will remain on containing the spread and rebuilding the economy.

With data science, pandemic control needs synchronization between several stakeholders, including the farming community, epidemiologists, animal science researchers, wet market traders, exporters, local businesses, and consumers. Connections between these important participants in the food supply chain will be critical for better data sharing and holistic risk assessments. Evidence-based policy advice requires data. Unfortunately, many stakeholders were flying blind throughout the pandemic and evidence has remained inconsistent , fostering doubt and uncertainty among consumers.

One can argue that recent pandemic has started a new era in which food safety oversight is more ubiquitous. This era will likely be defined by how holistic risks are considered and managed by the food industry. Risk management is no longer just about food safety, but rather the integrity of the entire system. From risks in farm fields, to conditions in which workers live, to how the entire supply chain can cope with the closure of a massive economic sector overnight.

At the beginning of the crisis, the food industry was facing uncertainties regarding the presence of COVID-19 in food production and distribution. With more research and science, the industry’s path moving forward will likely be clearer. More importantly, industry needs to anticipate how public health officials will manage risks related to a highly contagious virus. Pandemics are likely to happen again, mitigating your corporate risk to remain efficient with few interruptions is critical.

About the Author:

About the Author:

Known as the “Food Professor,” Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is Senior Director of Agri-food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University in Canada. Charlebois is a Professor in Food Distribution and Policy and is renowned for his work in agricultural and food policy. He has published over 500 peer-reviewed journal articles in several academic publications and has authored five books on global food systems.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants