The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

By Kristin Demoranville

From farm to fork, the food industry increasingly relies on networked devices and automated controls. A hacker breaching these operational systems (often called OT for “operational technology”) could be like an invisible contaminant slipping into the production line. In one real example, a cyberattack interfered with milk processing at a major dairy, halting operations for five days. The incident disrupted milk deliveries and contributed to a nationwide cream cheese shortage. Such cases show that a digital breach can swiftly become a food safety issue, triggering full-scale product recalls.

Cyber incidents in food production can cause a chain reaction of problems. An attacker might disable refrigeration monitors, alter pasteurization settings, or knock out power to critical safety systems. Any of these could let pathogens slip through or cause spoilage. Experts warn that a well-placed cyberattack could lead to contamination, for instance, by interfering with temperature controls during processing. If unsafe products reach the public, companies would have no choice but to issue recalls, just as they would for a bacterial outbreak. The difference is that in this scenario, the “germ” is a malicious piece of software or threat actor.

Real-World Breaches and Their Fallout

Recent global cases illustrate how cyberattacks have disrupted food supply chains and raised food safety alarms.

In the June 2021 ransomware attack on JBS Foods, the world’s largest meat processor, hackers caused significant operational disruptions across multiple countries. In the U.S., all beef plants were forced to shut down temporarily, raising concerns about meat spoilage and missed shipments. In Canada, plant shifts were canceled, and facilities were temporarily inoperative. In Australia, the company stood down approximately 7,000 employees and ceased operations at 47 sites. JBS ultimately paid an $11 million ransom. Though the company managed a swift recovery, the incident led to temporary meat shortages and highlighted the vulnerabilities in the global food supply chain.

Another case unfolded in October 2021 at Schreiber Foods, a major U.S. dairy producer. A ransomware gang struck over a weekend and demanded $2.5 million to restore systems.

This incident shows how digital sabotage can have food safety implications: if milk can’t be pasteurized on schedule, it may need to be discarded to avoid health risks. Schreiber resumed operations after five days, but those lost days carried heavy costs, including wasted food, lost revenue, and shaken confidence among employees and partners.

Cyber threats aren’t limited to meat and dairy. In February 2023, Dole Food Company fell victim to ransomware. The attack forced Dole to shut down production plants across North America and stop shipments. Shoppers in some regions found empty salad shelves where their favorite bagged greens should have been. Dole moved quickly, but the company incurred $10.5 million in direct costs due to the cyber incident.

Cyberattacks can cause enormous losses and divert resources from other priorities, including food safety programs.

Foodsafety and cybersecurity are two sides of the same coin in a modern food company.

The Chain Reaction of a Food Cyber Crisis

Why do cyber breaches cause such a chain reaction in food production? Firstly, modern food facilities are highly automated for efficiency. Production grinds to a halt when a key step is knocked offline. At Schreiber Foods, for example, the hack “affected their ability to receive raw milk,” meaning farmers had no place to send fresh milk during the outage. Even a brief interruption in agriculture can lead to waste and potential environmental issues from the disposal of spoiled inventories.

Secondly, a cyberattack often means that safety monitoring systems go dark. Many factories have digital sensors tracking temperatures, pH levels, and conveyor speeds to ensure products are made safely. If those sensors are compromised or feed faulty data, unsafe products could slip through. One industry report noted that a cyberattack could alter food safety settings, for example, by manipulating pasteurization controls and allowing contamination. In this way, a hacker can indirectly introduce a food safety hazard without ever touching the food.

Thirdly, the financial and reputational costs create their own shockwaves. A large food recall is expensive on its own, but add to that the cost of IT forensics, system rebuilds, downtime, and sometimes ransom payments, and the total skyrockets. JBS’s $11 million ransom was just a portion of the cost; the broader economic impact included lost production and even higher meat prices. Dole’s $10.5 million in losses likewise included technical recovery and lost operating income. These hits can also affect individual employees and entire communities.

Finally, there’s the trust factor. Aside from public confidence in a brand, when a cyber incident sparks a recall, it raises unnerving questions: “Was this contamination accidental or intentional?” or “Can we trust the company’s controls?” Communities may worry about broader food security if key providers are so vulnerable.

Building Resilience: Blending Cybersecurity into Food Safety Culture

For food industry leaders and safety professionals, these examples drive home a clear message: cybersecurity is now as essential to food protection as hygiene and testing. The good news is that building resilience against cyber threats doesn’t require abandoning core food safety practices – instead, it means extending that same rigor to digital systems. A strong food safety culture that includes cybersecurity might, for example, treat a suspicious email link like a biological hazard – something every employee is trained to recognize and avoid. In practical terms, that means training staff at all levels on basic cyber hygiene (analogous to personal hygiene in a plant), such as using strong, unique passwords and multi-factor authentication to lock down systems. These measures are like sealing a warehouse with a sturdy lock and key.

Another key step is to segregate and safeguard critical process controls. Just as raw ingredients are kept separate from cooked products to prevent cross-contamination, companies should separate their factory control networks from regular office IT networks. This limits the reach of malware if an office computer gets infected. Regular software updates and security patches are the digital version of equipment maintenance – they fix weaknesses (like a faulty valve or frayed wire) that hackers could exploit. Cybersecurity experts also urge food companies to perform routine security assessments and backups. Backups ensure that even if systems are encrypted by ransomware, you can restore operations without paying criminals.

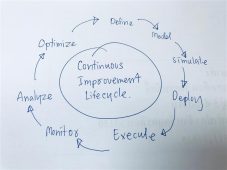

Perhaps most importantly, companies need an incident response plan that meshes with their food safety emergency plans. Many food businesses already have recall plans and crisis communication protocols. The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has published a Food and Agriculture Cybersecurity Checklist to guide organizations. It recommends steps like developing a cyber incident response plan, practicing it with tabletop exercises, and knowing who to call if a breach occurs. A well-drilled team that can contain a hack quickly is now as crucial as a fast-moving recall team for contaminated products.

In conclusion, food safety and cybersecurity are two sides of the same coin in a modern food company. A culture of safety now must encompass digital vigilance alongside cleanliness and quality control. Leadership should prioritize cybersecurity investments with the same urgency they give to pathogen reduction systems.It means fostering awareness that protecting a food plant from malware protects consumers just as surely as wearing gloves or hairnets. The food industry can strengthen its defenses by learning from recent cyber incidents and adopting robust preventive measures. The cost of a breach – in dollars, disruption, and danger – is simply too high to ignore.

About the author

Kristin Demoranville is a cybersecurity and risk management expert with over 25 years of experience in the tech industry. She is the founder and CEO of AnzenSage, a consulting firm focused on securing the critical infrastructure of food, agriculture, zoos, and aquariums. Kristin is also the co-founder of AnzenOT, a SaaS OT Cybersecurity Risk Intelligence platform purpose-built for cyber-physical systems. With a degree in environmental management and a research background in gorilla behavior, she brings a systems-thinking approach that bridges science, technology, and operational realities. Kristin specializes in OT/ICS environments and has become a trusted voice for sectors often overlooked in cybersecurity conversations. She also hosts the award-winning Bites & Bytes Podcast, where she leads thoughtful discussions at the intersection of food, technology, and cybersecurity.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants