The Psychological Secret to Employee Motivation Will Improve Food Safety

By Austin Welch

It’s an early spring morning on March 21, 2007, in the small town of Blakely, GA, and the quality manager arrived at his facility to begin the day.

He’s been pulling late nights and early mornings over the past few weeks; orders have been coming in faster than he and his team can get them out the door.

As he reviewed his paperwork, he saw that an order was due to go out that week but still hadn’t been tested for salmonella. It’s a big client, so he shoots off an email to the CEO asking how to proceed. A few minutes later he hears his email notification ding with a response from the CEO that changed not only the course of the food industry, but the lives of hundreds of families forever:

The role of the organization and its’ leadership is to create the conditions in which an employee can take values, attitudes, or regulatory structures, and internalize them.

“Sh*t, just ship it. I can’t afford to lose another customer.”

The response from Stewart Parnell, CEO of Peanut Corporation of America was clear: he placed financial gain above safety.

Food safety culture is defined by GFSI as the “shared values, beliefs and norms that affect mindset and behavior toward food safety in, across, and throughout an organization.”

Those norms are composed of the observable behaviors within an organization; and as we have started to recognize , food safety culture equals behavior. But what drives behavior?

Behavior is the manifestation of motivation. For a behaviour to occur, an underlying motivation must fuel it.

In the Peanut Corporation of America case, the motivation of the CEO became very clear when those emails surfaced.

While this is one of the viler examples of deplorable food safety culture, it helps to clarify this point. Motivation (fear of financial loss), leads to behavior (shipping known contaminated food).

Motivation → Behavior → Culture

Motivation = Behavior

This leads us to conclude that if we want to affect food safety behaviors, we must understand motivation, the “spark” that ignites behavior.

Before I began my research into motivation, I viewed it from a simplified “carrot and stick” viewpoint. Motivation was simply the use of positive or negative consequences to obtain a desired behavior. It seemed that motivation was “done to” employees.

Then, everything changed; I discovered the world of research under the banner of Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Developing an understanding of how “self-determined” behaviors are far more sustainable than “consequence-determined” behaviors shifted my entire approach to designing behavior-based education programs.

My aha moment could be summed up in a quote by Edward Deci (one of the co-founders of SDT) that:

As Edward Deci said, “The proper question is not ‘How can people motivate others?’ But rather, ‘How can companies create the conditions wherein people will motivate themselves?’”

How to Get Employees to Engage in Food Safety Culture (Even When You’re Not Watching)

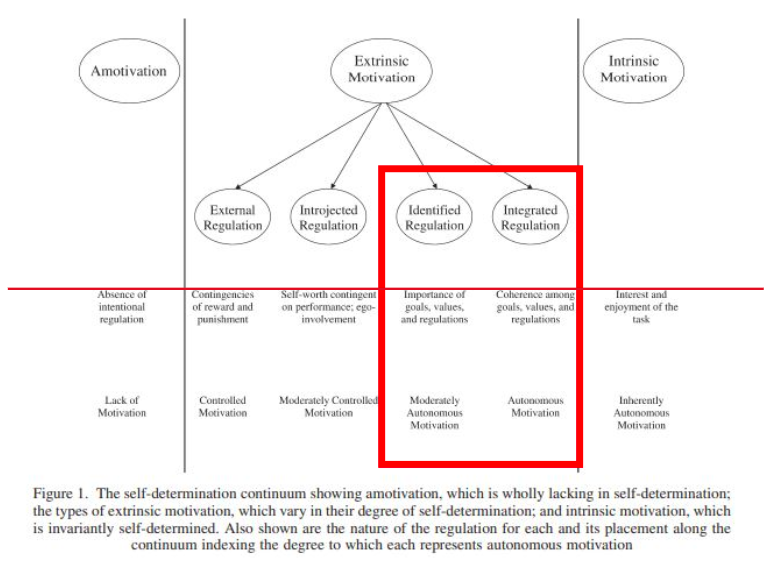

We can view motivation as a spectrum, ranging from a complete lack of motivation, all the way to intrinsic motivation, the internal drive to engage in an activity because it is a source of joy (i.e hobbies).

The role of the organization and its’ leadership is to create the conditions in which an employee can take values, attitudes, or regulatory structures, and internalize them. This transforms desired food safety behaviors into autonomous motivators. Simply stated, the employee engages in food safety behaviors even when the boss is not watching.

The gold standard would be to have every employee intrinsically motivated by the work that they do, but that is almost impossible. Instead, let’s look at the two highest forms of extrinsic motivation and how you can create the conditions that will increase autonomous motivation within your team.

With identified regulation behaviors, employees feel greater autonomy because they understand the importance that their work has concerning food safety. If food workers value their customers’ health and understand the importance of doing their share of unpleasant tasks for the customers’ wellbeing, the employee will feel relatively autonomous while performing such tasks, even though the activities themselves are not intrinsically interesting.

With integrated regulation behaviors, employees perceive food safety behaviors as an integral part of who they are. It emanates from their sense of self and is therefore autonomously motivated. If internalized, the employee would identify with the importance of maintaining their customers’ health, and those food safety behaviors will become integrated with other aspects of their jobs and lives. The profession of “safe food worker” will become central to their identity.

If employees can see their impact on the greater good, then they are more inclined to assign value to the tasks necessary to provide safe food.

Mission, Vision, and Values

This brings us to the organization’s role in defining the food safety goals and values that it seeks to internalize within its employees.

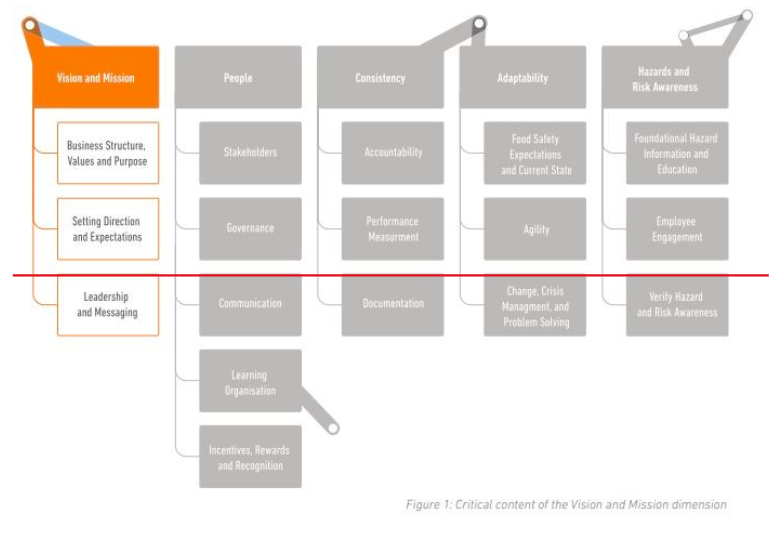

“Vision and Mission” is the first of the five pillars outlined within the GFSI Food Safety Culture Position Paper. “Vision and Mission communicates a business’s reason for existence and how it translates this into expectations and specific messaging for its stakeholders.”

In my experience, the two strongest transmitters of those expectations and specific messaging have been through top-level leadership commitment and education programs.

Top-Level Leadership Commitment: When employees hear a message about food safety come from the top echelon it reinforces that the company places a value on safety. Paul O’Neil, former CEO at Alcoa, set out to make that company the safest in America. When asked by reporters or shareholders for measures of success he would respond, “If you want to understand how Alcoa is doing, you need to look at our workplace safety figures.” He would often open factory meetings by pointing out the fire exits within the room. Paul O’Neil created the high-water mark for leadership commitment to safety instead of using it as a talking point. When top level leadership places a focus on food safety, it has a higher likelihood of trickling down to middle management, and to the frontline.

Education Programs: Employees must understand the unique value their specific position plays within maintaining food safety. This is critical if they are to integrate food safety behaviors into their daily work. Education programs must allow for exploration of critical thinking, self-defined goals, and responsibilities to help foster the autonomous motivation we seek.

Creating autonomous motivation will not come easy or quickly, but it will be necessary if we are to bend the curve of foodborne illness. Process, procedure, certification, audits; these are all great starts, but we all know that what will stop a potential recall is the eyes and ears of people that view themselves as the guardians of their customers.

About the Author:

Austin Welch is a learning designer, filmmaker, and researcher. Leveraging research from cognitive science, adult learning theory, and change management models; he designs behavior-based programs that strengthen the “people side” of food safety culture. His programs and films have been used as a cornerstone of innovative, global food safety culture programs at companies such as Hershey’s and Kerry Group.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants