Maintaining Food, Naturally

By: Suzanne Osborne, Ph.D

Lately, while shopping at my local grocery store, I have noticed the increasing number of food products marketed as organic or preservative-free. More and more, consumers are demanding green labels and ingredient lists they can understand. Yet food safety — preventing food spoilage and contamination from microbial pathogens — must remain a top priority for food producers. The food safety industry faces many challenges if it is to transition away from the use of refined chemicals toward more label-friendly preservatives.1

Antimicrobials for Food Safety

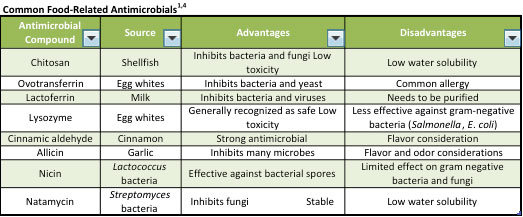

“Natural” food-preservation techniques require antimicrobial treatments that come in the form of whole food ingredients or extracts; they also require innovative methods for applying these natural antimicrobials to the product. Research has already discovered several whole-food ingredients with antimicrobial abilities (see Table 1).

It is hard to determine which food antimicrobial is best. This is because there are multiple ways to test whether a food antimicrobial is working and the findings are not always easy to directly compare. It does appear that combining several natural antimicrobials is often the most effective at limiting product contamination and ensuring food safety.2

Complicating these choices, though, is the fact that the activity of many natural antimicrobials can be altered by the food product to which they are applied, the environmental conditions and the type of packaging.3,4,5 Strategies to limit the interaction between a natural antimicrobial and the food environment would greatly increase the ability to use these whole foods to prevent contamination and increase food safety.

Encapsulating Antimicrobials for Food Safety

Researchers including Dr. Matthew Taylor of Texas A&M University have been developing encapsulation technology to entrap antimicrobials. Dr. Taylor believes that encapsulating natural preservatives in tiny, lipid (fat)-based enclosures called liposomes allows for “protection of the antimicrobial compound from degradation by the food product or… allow[s] for a longer dose effect against the foodborne pathogen.” These structures are flexible and allow the preservatives to release more gradually compared to when they are added unencapsulated.

Dr. Taylor points out that lipid-based capsules can be influenced by acids, light, sound and temperature, properties that researchers have taken advantage of to create “release-on-demand” systems. There is evidence that encapsulating natural preservatives is effective: encapsulating nisin or lysozyme increased their ability to fight off Listeria monocytogenes, a disease-causing bacterium found in food, for example.6

Although liposome-encapsulation technology is already commercially available, there are still challenges to be overcome. Liposomes are made entirely from natural biological membranes, but little is known about their interactions with food.7 “There are sometimes labeling concerns that might prevent incorporation of liposomes because of how the food must then be labeled… there are great concerns over the safety of food-applied nano-scale technologies,” cautions Dr. Taylor.

Meeting the Demand for Safe, Natural Products

The food safety industry needs to keep up with consumer demand for natural, label-friendly, minimally processed food products. As we continue to discover the ways in which foodborne bacteria can be transmitted to consumers, we are also faced with the challenges to changing regulations. The development of antimicrobials must remain a continuously evolving industry. A great deal of research into natural antimicrobials and effective delivery systems has already been conducted, but much more is needed to determine the best combinations for individual food types. Consumers’ demands to know what is in their food continues to evolve, but their desire for safe food remains constant.

References

-

-

-

- Davidson, P.M., et al. Naturally Occurring Antimicrobials for Minimally Processed Foods. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 2013 4:163-190.

-

- Ibid.

-

- Ibid.

-

- Juneja, V.K., et al. Novel natural food antimicrobials. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 2012 3:381-403.

-

- Cutter, C.N. 2002. Microbial control by packaging: a review.Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 42(2):151-61.

-

- Were, L.M., et al. 2004. Encapsulation of Nisin and Lysozyme in Liposomes Enhances Efficacy against Listeria monocytogenes.J Food Prot. 67(5):922-27 indianpharmall.com.

-

- Taylor, T.M., et al. 2005. Liposomal nanocapsules in food science and agriculture.Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 45(7-8):587-605.

-

-

About the Author

Dr. Suzanne Osborne’s expertise is in the field of host-pathogen interactions and foodborne bacteria. She obtained her doctoral degree at McMaster University and worked as a Research Fellow at the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto). She has received numerous awards for her research. Suzanne currently does freelance science writing and grant writing.

To have more articles like this emailed to your inbox, become a GFSR Member today!

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants