Bacteriophages: Powerful Weapons in the Arsenal Against Foodborne Illness

Posted: Tuesday, August 14 2019

By Lois Harris

Bacteriophage-based products have been approved for use in food applications and are increasingly commercially available in many countries, including the U.S., Canada, and Israel. Most of these phage products are water-based concentrates, free of chemicals and preservatives, and are not genetically modified. But how do they stack up against standard antimicrobial processes like pasteurization, irradiation, chemical disinfectants and high-pressure processing (HPP)?

Dr. Alexander Sulakvelidze feels that phages represent a highly effective tool to prevent foodborne illness and recalls. Sulakvelidze is Executive Vice-President and Chief Scientific Officer of Intralytix, a biotechnology company based in Baltimore, Maryland that focuses on discovering, producing and marketing bacteriophage-based products.

“Phages in our products are 100 per cent natural. Phages are already a normal part of the foods that we eat,” he says. “And they can be very effective in specifically targeting foodborne bacteria in our foods. It’s the gentlest, most natural approach for ensuring the safety of foods.”

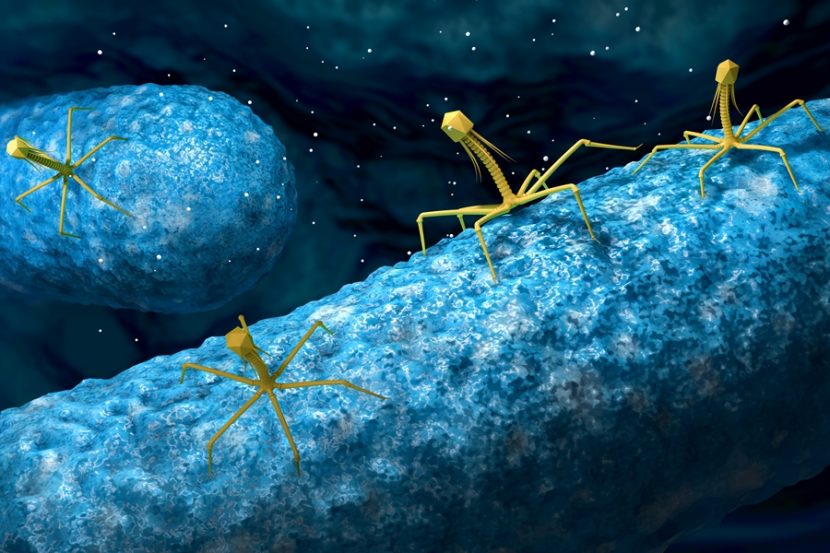

Phages occur naturally all around us in the environment, on fresh foods and in the intestinal tract of our bodies. They are arguably the oldest organisms on earth and they act like viruses, targeting and destroying—or significantly reducing —specific pathogens like Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli and Shigella in various foods.

Phages occur naturally all around us in the environment, on fresh foods and in the intestinal tract of our bodies.

Environmentally Friendly, Versatile and Cost-Effective

Unlike other antimicrobial processes, phage products don’t kill all bacteria indiscriminately. They kill only their targeted specific bacteria, leaving the “good” bacteria intact to do their jobs. Phages are also non-corrosive and, therefore, easier on equipment than chemical disinfectants. Many phage biocontrol products are certified kosher, halal and organic and don’t alter the taste, appearance or smell of the food.

What’s more, the product can be used at various points along the food processing system. Phages can be sprayed on fresh produce, applied to livestock just prior to slaughter, used as a cleaner on equipment surfaces and employed as a treatment for ready-to-eat meals. They also cost less than many other antimicrobial methods currently employed by the food industry – typically, between one and three cents per pound of food treated, compared to, for example, 10 to 30 cents a pound for irradiation or HPP.

Drawbacks

Phage usage is not without drawbacks, however. One of the most attractive properties of phage biocontrol could also be their biggest limitation. Their specificity means that a phage preparation to combat one kind of bacteria (e.g. Listeria) won’t kill other pathogenic bacteria (e.g., Salmonella) that may be also present. Combining phage products can deal with this situation. In addition, many food products are plagued by one kind of pathogen – for example ground beef with E. coli or smoked salmon with Listeria monocytogenes.

Phages also need to be refrigerated at between two and eight degrees Celsius and can be rendered ineffective if combined with chemical sanitizers. Also, while they significantly reduce targeted bacteria (typically by 50 to 80 per cent), they don’t necessarily kill everything.

“That reduction is plenty sufficient for real life situations,” Sulakvelidze says, distinguishing this from laboratory conditions. “Normally, food is not contaminated with trillions of cells of one pathogenic bacterium – usually it’s 100s or 1,000s of cells, and phages can deal with those numbers very effectively.”

Another challenge is that phage-resistant bacteria could emerge in the future. Sulakvelidze says he recommends using cocktails of phages, rather than using a single phage. He also says that it’s a good idea to treat foods with phages only at the end of the production process – for example, just before packaging – instead of spraying phages at the beginning of the food processing chain, say, in a chicken barn – which also mitigates the chance of resistant bacteria developing.

About the Author

Lois Harris is principal writer and editor at Wordswork Communications, and she has been part of GFSR’s editorial community since 2017. She brings a strong background in writing for a number of food manufacturers, non-profit organizations, governments and universities to her work on GFSR’s behalf, and has a keen interest in the food safety issues that affect consumers and industry.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants