E. coli O157:H7 Outbreaks: When Science Speaks but No One Listens

By: Suzanne Osborne, Ph.D

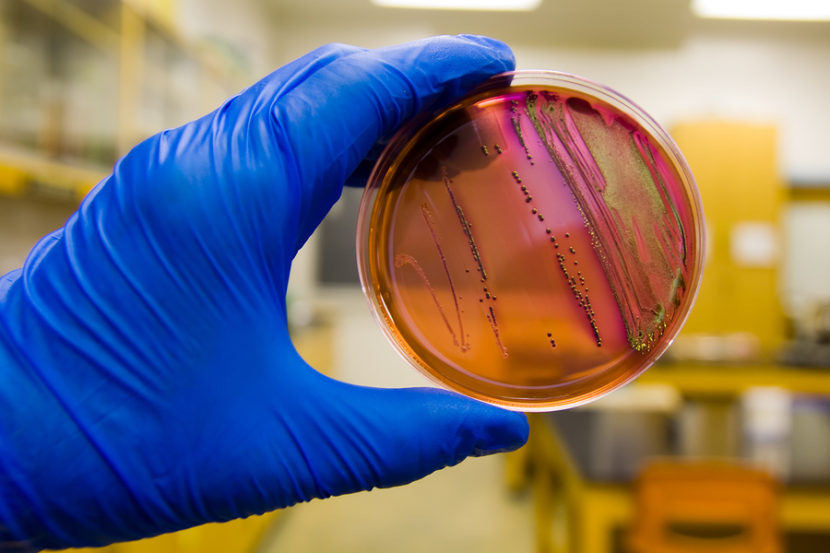

On September 3rd, 2012, a routine inspection of Canadian beef crossing the American border snowballed into one of the largest food recalls in Canadian history. Within 12 days, more than 1.5 million pounds of beef originating from XL Foods Inc., located in Brooks, Alberta had been recalled due to contamination with Escherichia coli. As one of Canada’s largest beef processing plants, XL Foods’ distribution list included over twenty countries. To date, sixteen people have reported illness due to the contamination with E. coli O157:H7 (1). Resulting infections typically cause severe cramping and bloody diarrhea caused by the destruction of cells lining the intestine (3,4) and, in some cases, can lead to haemolytic uraemic syndrome, potentially causing rapid kidney failure (4). Cattle are the major source of E. coli O157:H7. These bacteria can attach to the wall of a cow’s intestine without causing disease in the animal, enabling them to shed the bacteria into the environment, contaminating other cattle, groundwater and vegetation (2,3,4). The ability to identify infected cattle is extremely limited.

In the United States the annual economic burden includes $405 million in health care, $2.7 billion cost to the food industry (decreased demand, product loss and plant down time) and $300 million in litigation and insurance liability. With numbers like these, one would expect a sophisticated outbreak prevention system to be in place. The real problem, however, is that current strategies to prevent outbreaks are responsive instead of proactively preventive; they focus on limiting cross-contamination and isolating infected products at the plant rather than keeping infected cattle from entering the plant in the first place.

Canadian-based Bioniche Food Safety has a solution to this problem. It has licensed econiche, a cattle vaccine developed based on Dr. Brett Finlay’s research at the University of British Columbia. The vaccine works by immunizing cattle against the proteins used by E. coli O157:H7 to attach to their intestinal wall (5). This strategy prevents cattle from carrying E. coli and limits their ability to pass it on to humans. It also keeps bacteria from being shed on the farm, reducing the chances of E. coli O157:H7 entering groundwater and contaminating crops. With all the potential benefits, why hasn’t everyone started using the vaccine? No one wants to foot the bill.

At a cost of $6 per cow for the vaccine, the estimated return on investment is 3:1. Although a limited number of farms have begun implementing the vaccine, it hardly seems fair for farmers to foot the bill when they are not typically absorbing the costs of an outbreak. For universal vaccine implementation, Mr. Rick Culbert, President of Bioniche Food Safety, said we need “more public outcry to force political involvement…health must trump agriculture.” Bioniche emphasizes that vaccination cannot replace but will compliment current food safety practices to “reduce the risk to public health.” Instances such as the industry-mandated Salmonella vaccine for chickens in the United Kingdom suggest the massive potential benefits of this approach. “It just makes perfect sense..” says Mr. Cultbert.

At a cost of $6 per cow for the vaccine, the estimated return on investment is 3:1. Although a limited number of farms have begun implementing the vaccine, it hardly seems fair for farmers to foot the bill when they are not typically absorbing the costs of an outbreak. For universal vaccine implementation, Mr. Rick Culbert, President of Bioniche Food Safety, said we need “more public outcry to force political involvement…health must trump agriculture.” Bioniche emphasizes that vaccination cannot replace but will compliment current food safety practices to “reduce the risk to public health.” Instances such as the industry-mandated Salmonella vaccine for chickens in the United Kingdom suggest the massive potential benefits of this approach. “It just makes perfect sense..” says Mr. Cultbert.

One thing is clear; we have the technology to reduce the likeliness of E. coli outbreaks like that seen at XL Foods. Science has spoken. Are you listening?

REFERENCES

(1) Canadian Food Inspection Agency. CFIA Investigation into XL Foods Inc. (E. coli O157:H7) http://www.inspection.gc.ca/food/consumer-centre/food-safety-investigations/xl-foods/eng/1347937722467/1347937818275.

(2) Public Health Agency of Canada. E. coli. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/fs-sa/fs-fi/ecoli-eng.php

(3) World Health Organization. Fact Sheet: Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheet/fs125/en/

(4) Chase-Topping, M., et al, 2008. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 6:904-912.

(5) econiche. Cows Can Help. http://www.econichevaccine.com/en/?page=home

(6) Allen, K.J. et al 2011. Can. J. Vet. Res., 75(2):98-105.

(7) Potter, A.A. et al 2004. Vaccine, 22(3-4):362-9.

About the Author

Dr. Suzanne Osborne’s expertise is in the field of host-pathogen interactions and foodborne bacteria. She obtained her doctoral degree at McMaster University and worked as a Research Fellow at the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto). She has received numerous awards for her research. Suzanne currently does freelance science writing and grant writing.

To have more articles like this emailed to your inbox, become a GFSR Member today!

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants