Early Crisis Communication Safeguards Companies During Food Industry Recalls

By Janet M. Riley

The U.S. food supply is among the safest in the world – and getting safer. That’s why news of failures can rattle consumers. Food recalls, especially if they involve illnesses, can damage consumer trust quickly and irreparably, which is why early efforts to build trust, plan and prepare should be fundamental business practices. Enter crisis communication.

Trust cannot be built overnight. It is cultivated through sustained interaction and thoughtful and deliberate engagement. Food companies must introduce consumers to their companies, their products, and their practices long before a crisis occurs. Sustained efforts to share your food safety programs, policies and innovations are essential and communicate the seriousness with which you take food safety every day of the week – not just when a problem occurs.

Build Trust Early

Too often, companies haven’t taken the time to develop the kinds of messages that support their food safety story – but it’s one of the best investments you can make.

Food recalls and foodborne illness outbreaks are two situations for which every company in the food industry should plan.”

Messages that will build trust should be:

- Use simple terms and comparisons that people can understand and retain. A five-log reduction means nothing to a consumer, but a processing line that looks like an operating room does. A food safety record that leads the industry might also build confidence.

- Tailored to stakeholders. A message to your investors will need to be different than a message to your consumers. Write tailored versions of key messages now.

- We live in the visual world of YouTube and Reels, and we must accept that and communicate in a way that suits this world.

- Given the competition for consumers’ attention, a single press release or short video is insufficient. You need a regular, planned program for communication that will repeat core messages in new, interesting, and visual ways.

- Told as stories. Effective storytelling is a proven technique that connects your message with the listener by triggering the release of oxytocin in the brain. You may not think you have interesting stories to tell but given how little consumers know about how food is produced and processed, you have an endless supply.

Write the Plan

At the same time, you work to build trust, it is essential to consider the crises you are most likely to encounter and prepare for them ahead of time. Food recalls and foodborne illness outbreaks are two situations for which every company in the food industry should plan, and the act of writing a plan will build your crisis response muscle.

Remember that when bad news hits, everyone wants to know how they themselves could be impacted, so stakeholder specific messages are a must. For example, in a recall:

- The consumer wants to know if food is safe to buy and consume.

- The employee wants to know if his job is safe and how the incident may affect his role.

- The stockholder wants to know what impact the recall will have on the company and the stock prices.

Thinking through these messages without the pressure of a real, live crisis will result in better communication.

Finally, consider what outside resources you may need in a crisis, like a public relations firm, a lawyer, or a laboratory. Identify partners you can trust in a crisis before you need them.

Practice and Train

Tabletop drills that bring key players together to engage in a scenario are essential and reveal both strengths and vulnerabilities in your plans.

It’s also important during the preparedness phase to capture images and video from your best day that you can use on your worst day. During a crisis, your plant may not be operating normally, yet the media will still want images. Capture video and images that show your operation in its best light and share them with the media.

Your plan must be supported by a trained team. People throughout the company have roles to play in communications, and “peacetime practice” is essential to effective crisis communications. Don’t limit communications training to your spokespeople. Media training is a way to learn to control your message in a variety of situations, from dialogues with inspectors to presentations to customers. This training can be invaluable throughout your company.

Lead Knowing You’re Prepared

When a crisis hits, many people want to avoid commenting and wait for the crisis to pass. But silence is never an effective strategy in a crisis. If you have built trust, developed plans, drilled and practices, you are very prepared to lead a timely and effective crisis response.

There are several key ingredients:

- Defined internal processes: Decide in advance who is on the crisis response team, when that team will meet and who signs off on internal and external communications. This will help reduce chaos and confusion.

- Speed of response: Silence creates a vacuum that will be easily filled with speculation. It is essential to make a statement to internal and external audiences as soon as reasonably possible or tell stakeholders when you expect to have details.

- Transparency: Be as transparent as possible. Say what you can say and admit what you don’t know or are still investigating. This will also help reduce speculation.

- Effective, available communicators: It may be your Ph.D. food scientist – or it may be someone else. A good spokesperson must understand the situation, be able to communicate simply with urgency and sincerity. Both authority and authenticity are important in a crisis.

- Steady flow of information to stakeholders: Crises by their nature involve chaos. Each stakeholder should be hearing the same message, but one that is tailored to their needs and provided at regular intervals. They should be told when to expect updates in any developing situations.

- Media and social media scans/corrections: Just as a company in crisis may feel chaos, reporters under pressure to cover a crisis may feel rushed and pressured, which can lead to mistakes. It’s important to scan media, identify mistakes early and seek corrections.

Reputation Repair

The final phase of crisis management is reputation repair. It is essential post-crisis to assess the damage that was done and plan to communicate any changes you are making. Less news coverage does not mean things are back to normal. You are far better off briefing stakeholders on what you learned and what you changed because of the crisis.

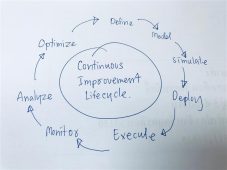

Crisis preparedness is never a “one and done” – it’s a muscle that must be toned and strengthened regularly. Making trust-building, crisis planning, and preparedness priorities will help keep your company strong.

About the Author:

Janet Riley is an expert communications strategist, professional facilitator and media spokesperson and trainer. Today, she operates her consulting practice in Washington, DC, leveraging five years of leading communications at Maple Leaf Foods in Toronto and 28 years leading public affairs and serving as the meat industry spokesperson at the North American Meat Institute in Washington. She has also been the face of the meat and poultry industry in response to some of the industry’s most challenging crises, including the first U.S. case of BSE in 2003. Riley is also a well-known food safety author. She earned a master’s degree in organizational development and leadership at Saint Joseph’s University and a bachelor’s degree in journalism at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants