Who’s Responsible? Rethinking Food Safety Policy in a Globalized Era

By Keith Warriner

Food safety policy has evolved alongside global trade, emerging risks, and technological advancements. While regulations are essential for enforcing standards, they can sometimes shift responsibility away from food businesses and onto government agencies. With artificial intelligence and data-driven monitoring systems playing an increasing role in food safety, policymakers must strike a balance between oversight and industry leadership to ensure a safer, more resilient food system.

Food policy is the foundation of any civilization that aims to ensure food is available, affordable, authentic, and safe. History has numerous examples of failure to implement a sound food policy, leading to riots and even the collapse of regimes. The most notable was the French royal house when Marie-Antoinette was accused of advising the peasants to eat cake if they didn’t have bread.

As populations became urbanized during the Industrial Revolution, the dependency on the government for greater oversight over food production and distribution grew in importance. Governments increased their focus on promoting agriculture, reducing food fraud, and protecting the population from foodborne hazards.

Food policy is the foundation of any civilization that aims to ensure food is available, affordable, authentic, and safe.

Then, with the introduction of rationing in WWII, food policy shifted to influence the population’s diet.

Food policy as a food safety tool

Policy is a means for government or other organizations to guide a population’s behaviors, actions, and practices to achieve an identified goal. The scope of policies can range from being focused within a single organization to broadly guiding the global agri-food sector. Food safety policies are achieved with guidance, voluntary directives, or regulations. Although safety is part of food policy, it tends to be more in the background than nutrition and food security issues.

While non-government organizations (NGOs) can’t pass laws, they can suggest standards that align with policy, such as Codex Alimentarius. Regulatory bodies can guide the industry toward achieving food safety by implementing standards and influencing regulations. However, even today, most consumers hold the government responsible for ensuring food safety and for providing the food industry with the requisite knowledge.

Globalization of food safety policy

Politicians, administrators, and lawmakers run the government, so they could be forgiven for not understanding the intricacies of the agri-food sector. Consequently, in developing food safety policy, there is a tendency to observe initiatives from other jurisdictions and then adapt to a national policy. Such an approach also ensures that trading partners are aligned, thereby providing assurance, to some extent, that traded goods are safe.

A global approach to food safety policy was proposed in the 1920s, although countries were not feeling particularly cooperative at that time. After WWII, the United Nations was established, and the Codex Alimentarius was developed through a collaboration between the Food Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Trade Organization (WTO). The main activities of Codex are to devise globally recognized standards through a combination of science-based risk assessments and expert opinion that regulators then use to devise food safety policy.

Regulations and guidelines as a food safety tool

Different jurisdictions have developed regulations and guidelines using Codex Alimentarius standards as a foundation. For example, the United States places heavy emphasis on regulations supported by guidelines, and its policies are less reliant on voluntary practices. This approach was further underlined by the introduction of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), which was supported by the FDA Food Code, a document that is over 700 pages long and is a guide on how to meet the regulations.

One of the revolutionary parts of FSMA was the introduction of Hazard Analysis and Risk Prevention Controls (HARPC). Since the HACCP – or Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points – approach had been the primary food safety management system since its introduction in the 1990s, HARPC was considered disruptive.

The policy decision to introduce HARPC was based on the limitations of HACCP in reducing foodborne illness and incidents. HACCP is focused on the “Critical Control Points,” and many HACCP plans were generic in nature and not implemented as written. In contrast, HARPC focused more on individual facilities and how to spread food safety preventative controls across all activities. In many ways, HARPC was closer to the foundation of the Codex Alimentarius principles and the European approach to food safety that considers all aspects of food safety (good manufacturing practices, good agricultural practices, and preventative controls, etc.) of which HACCP was a part.

However, HARPC brought confusion and uncertainty within the United States and with its trading partners. Within Canada, the need for modernization was recognized, so they used HACCP, added preventative controls and retained the prerequisite program and HACCP principles. Nevertheless, the introduction of Safe Food for Canadian Act (SFCA) regulations brought further confusion, especially for small and medium enterprises that were now required to undertake risk analysis and other steps to secure a license to operate.

The key reason for leveraging laws and regulations to enact policy is that it places regulators in the driver’s seat regarding food safety. However, it also undermines the confidence of the industry to ensure food safety. This is especially the case with small and medium enterprises that may not have the resources to meet regulatory standards. In some ways, the regulators are reluctant to introduce new regulations because governments will divert resources to training and funding inspectors

Industry initiatives in food safety policy

Industry cannot make regulations or set standards that, at a minimum, do not align with those set by regulators. Yet, some of the most successful food safety initiatives have been industry-led. For example, introducing HACCP was only possible with industry participation, especially in providing regulators with knowledge and inspection models. The introduction of Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) recognized schemes elevated HACCP to meet a standard in implementation and encourage continuous improvement.

The auditing standard has been questioned under GFSI, but auditors are more effective educators than government inspectors. The wide adoption of GFSI underlines that industry initiatives are impactful, given that the participants implementing the schemes are those involved in its development. Although public comment is short during the development of regulations, these are to identify exemptions to the policy rather than development.

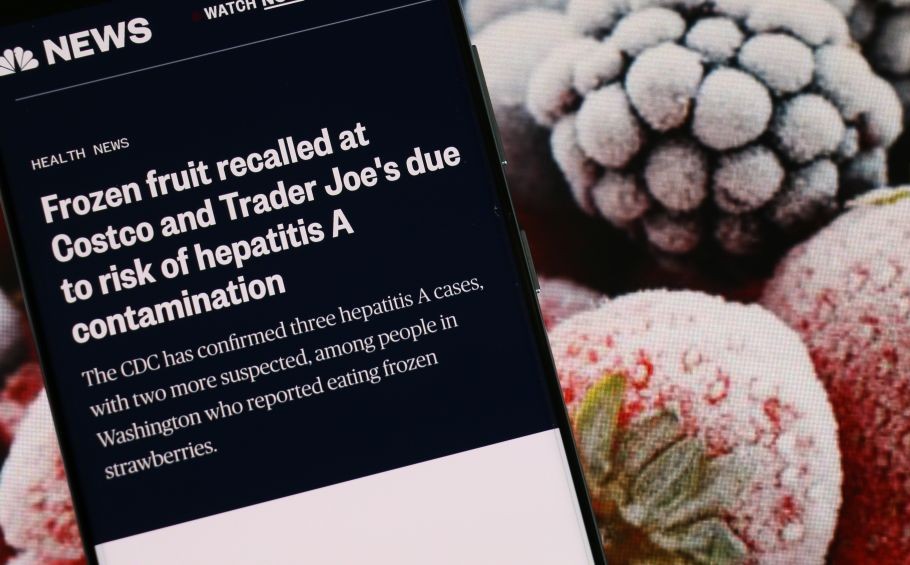

How to measure food safety policy success

An ongoing challenge with food safety policy is how to measure success. Various approaches can be applied, such as evaluating the prevalence of foodborne illness. However, foodborne illness is less than reliable. A further metric could be the number of foodborne illness outbreaks and/or product recalls. Here, the assumption is that a reduction in the number of recalls and outbreaks reflects the policy’s success. However, as surveillance and diagnostics become increasingly advanced, the probability of detecting outbreaks or contaminated products increases. It could then be argued that a seeming rise in recalls or outbreaks reflects better data collection.

A more direct measure of success can be found in the inspection and audit reports collected from Food Business Operators (FBOs), as these highlight the level of non-compliance over time. This represents an extension of the Establishment-based Risk Assessment (ERA) that applies 16-point criteria to identify facilities that need inspection resources. The FDA operates a similar system based on the same technology. The ERA system is still in development, yet when coupled with greater data sharing and artificial intelligence, the principles of the system could provide a means of monitoring the agri-food sector to directly determine the impact of food safety policy.

Rethinking food safety policy

Food safety policy has changed over the years with the advent of increased trade, emerging pathogens, new technologies, and approaches to inspection/auditing. Nevertheless, those who produce or process the food are ultimately responsible for its safety and quality. Regulations have been the main tool applied to implement policy, though this takes responsibility from the FBOs in some regards. There will always be a need for regulations to set limits, although industry initiatives along with advanced technologies based on AI should be explored.

About the Author:

Dr. Keith Warriner is a researcher in the Department of Food Science at the University of Guelph. Warriner is a professor with extensive expertise in pathogen control and foodborne illness prevention, has published over 100 scientific papers and served as president of the Ontario Food Protection Association. Lara J. Warriner and Mahdiyeh Hasani also contributed to this article.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants