Preserving Food Quality: The Critical Role of Packaging in Safeguarding Food Safety and Sustainability

By Sasha Matera-Vatnick

Consumers perceive value in transparency from food and beverage companies, and one area that has become top of mind for consumers is the sustainability implications behind the packaging of food and beverage products they purchase. Packaging plays a critical role in food safety and preservation by acting as a physical barrier, prolonging shelf life and alleviating environmental impact by reducing food waste. Packaging sustainability is a multifaceted topic given the interplay of disciplines, such as material science, food chemistry, food microbiology, supply chain, government regulations, consumer behavior, and increasingly, information science, among others.

A zero-risk approach to food production could have an undesirable effect on the environmental impact and nutritional quality of food.

We see the term ‘sustainability’ in the media spotlight frequently, but it means different things to different people. The Brundtland Report from the Swiss Office for Spatial Development defined sustainability in terms of meeting “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Brundtland divides issues into three categories: environmental, financial, and societal. As we reflect on the complex intersection of safety, packaging, and sustainability, it is useful to put it into the context of one of these pillars and to consider the interplay with the other two.

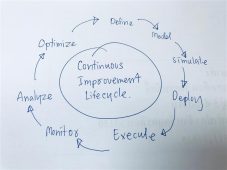

Over the years, food safety and packaging engineers have collaborated with and borrowed from the fields of ecology and information sciences, allowing for a focus on the system, and ways to optimize it. Ecology and information sciences find great utility in feedback mechanisms (or loops) to sustain and augment learning over time.

For example, monitoring the food production environment more frequently provides a more sustainable strategy than confirming contamination after the fact. If we look back at pre-FSMA food safety regulations, we see an approach that was more reactive: a problem is identified, and so it is addressed – another fire extinguished. These transdisciplinary perspectives have led to a shift towards systems thinking in food safety and food quality. This requires vigilance, through regular monitoring so that we learn not only when issues arise, but we can also understand how the system is working all together.

Sustainable packaging encompasses several approaches towards maintaining food safety and preventing food waste, including but not limited to: biodegradability using biomaterials; active packaging; recyclability; reduction of packaging weight for lower freight costs (financial and environmental), among others. Packaging must also significantly reduce the risk of food safety becoming compromised during a product’s lifecycle, from production to consumption to disposal. It is essentially unattainable to achieve zero risk of food borne harm to consumers. A zero-risk approach to food production could have an undesirable effect on the environmental impact and nutritional quality of food. The term “residual risk” is more appropriate, emphasizing context and boundaries of the system rather than a critical limit.

Given shifting consumer preferences and environmental concerns, packaging research and applications will need to focus on innovative solutions that prioritize sustainability, a food systems approach to food safety, and lifecycle efficiency.

In the trend towards consumers’ demand for “clean label” products, recent developments in nonmigratory active packaging show potential for reducing food waste and additive use, but do not address the broader issue of plastic packaging waste. Plastic packaging is valued for its “inert nature (unlikely to interact with food components) and ability to keep structural integrity until disposal.” This has led to a shift towards paperboard-based cartons, which must be coated for food safety reasons given the porosity of paper. Although the processing of paper as a raw material tends to be “pollution-intensive, paper being derived from renewable sources, being biodegradable, and being perceived to be more widely recyclable than plastic makes it generally more appealing to the average consumer. However, the combination of paper, plastic and aluminum laminates makes the recycling process more complex and costly given the separation of layers needed. When looking at the bigger picture, the entire supply chain or lifecycle of packaging, the options that seemed compelling from a sustainability standpoint might not be as sustainable in the current industry context.

From collaboration between the fields of soil science, microbiology, plant sciences, and economics has sprung the Circular Bionutrient Economy (CBE) model. The emphasis is on monitoring a food system for opportunities to be more efficient and to be more granular and contextual with definitions of waste and recyclables. In this way, a CBE or systems approach fosters simultaneous attention to the three pillars of the Brundtland report.

The New York State Packaging Reduction Act is currently under consideration, and it prescribes that food companies more clearly articulate how their packaging programs take a systems perspective. The act states that companies “shall” educate consumers on the three pillars and how packaging type impacts their interdependency and balance. Education and outreach surrounding packaging sustainability and the life cycle of the packaging is also emphasized in the proposed bill.

Another type of innovation changing how we optimize sustainability is being led by data science. Cornell Tech Professor Deborah Estrin is conducting research using “small data,” the collection of data from daily patterns, which gives rise to what we know of as “big data.” Instead of relying solely on cause and effect, as has historically been the case, we could leverage tools driven by AI to continuously gather quality control, consumer feedback and packaging optimization data. Such an approach could shed light on how food system changes happening in real time are impacting the sustainability and stability of the food system.

More effective communication and collaboration between the food industry, packaging companies, research universities, data scientists, NGOs, regulators, and consumers are still needed to make significant strides towards safer, stable, and more sustainable packaging options. We could achieve more effective decision-making and create a clearer path towards a more sustainable circular economy by digging deeper into the interplay between the disciplines discussed. Nevertheless, acknowledging these issues and the shift in our previous perceptions serves as a sustainable foundation for future progress.

About the Author

Sasha Matera-Vatnick is the R&D, Quality & Compliance Manager at Three Trees, a plant-based milk company, and previously worked in Food Safety & Quality at Cargill. She graduated from Cornell University with a B.S. in Food Science, where she became HACCP and SQF Certified.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants