The Vital Role of Non-Food Suppliers in Food Fraud Prevention

By John Spink

If you sell products to the food industry, then you ARE in the food industry and ARE required to meet food safety compliance requirements. A required – not optional – part of that compliance is for food fraud prevention. While you might think your risk is so low that it doesn’t apply to you, it is a compliance requirement for everyone.

This requirement applies to non-food suppliers to the food industry, including packaging, transportation, warehousing, storage, distribution, processing chemicals, industrial oils, pest control, cleaning services, laundry, and related maintenance parts. Fortunately, the food fraud vulnerabilities are probably few and very low. After you create the prevention strategy, the updates will usually be very simple and quick.

Food Fraud Unveiled

Food fraud is intentional deception for economic gain using food. This could be any fraud act, such as horsemeat illegally substituted for beef, melamine in infant formula and pet food to deceive protein tests, or a truck washing company not thoroughly cleaning your tanker between shipments.

The nearly universally adopted food safety management systems (GFSI through FSSC 22000, SQF, BRCGS, IFS, and others) include food fraud requirements. Each and every supplier to a food company is required to have a system in place, including a Food Fraud Vulnerability Assessment (FFVA) and a Food Fraud Prevention Strategy (FFPS). One type of FFVA is a simplified version referred to as a Food Fraud Initial Screening Tool (FFIS). Other food safety or HACCP requirements exist, such as in the US Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA).

The food manufacturers and the food auditors continue expanding the breadth and depth of evaluations. Food fraud compliance is a critical growing focus.

Non-Food Suppliers to the Food Industry

If you sell products or services into the food industry, then – at least to some degree – you have a food fraud compliance requirement. If you sell to the food industry, then you ARE in the food industry, and you ARE held accountable for food fraud compliance. Non-food suppliers to the food industry include packaging, transportation, warehousing, storage, distribution, processing chemicals, industrial oils, pest control, cleaning services, laundry, and related maintenance parts. Their vulnerabilities may be much lower than for a food manufacturer. Nevertheless, there could be concerns, and it is a compliance requirement.

While you might think your risk is so low that it doesn’t apply to you, it is a compliance requirement for everyone.

There is often an essential and fundamental question of ‘why do you care?’ Yes, the bottom line is the bottom line, and doing anything has a cost. You care because you want to comply with laws and regulations, you want to avoid recalls, you want to limit your legal liability, and you want to be able to stay in business. Also, most fundamentally, you do not want to get cheated by suppliers or criminals.

Case Studies & Examples

Fortunately, there are very comprehensive and accessible training and resources. Food fraud prevention has been well-researched, and many methods have been refined and optimized for specific industries or applications.

Case Study: Bulk Liquid Food Trucking Association

Last month, the Bulk Liquid Food Trucking Association organized a workshop during which a sixty-minute overview of food fraud prevention was offered, and the audience was taught how to conduct an industry-level Food Fraud Initial Screening (FFIS).

By the conclusion of the workshop, the two matrices in the FFIS Primer Document had been filled in, and the final corporate risk map for the entire industry was established. Due to the unique nature of their role as transportation suppliers, the group faced fewer traditional food fraud vulnerabilities. Instead of handling raw ingredients or cooked products, their responsibilities focused on pumping equipment and cleaning services. Members of the association already possessed a high awareness of the vulnerability associated with tank washing between deliveries. During the discussion, they also raised questions concerning the cleaning of personal protective equipment, including gloves. Queries regarding whether drivers changed gloves between deliveries and how they managed gloves that might accidentally fall on the ground during a delivery were explored. These questions were framed in the context of product safety and quality.

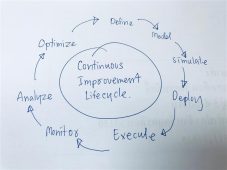

As a result of this workshop, the association now has a standardized method for assessing the severity of issues and quantifying the adequacy of cleaning procedures and monitoring or control systems.

Case Study: BRCGS Gap Analysis

At the end of September 2023, a ninety-minute food fraud gap analysis seminar was held. It was comprised of a set of 10 to twenty questions designed to provide a snapshot of food fraud prevention compliance. The key takeaway from the presentation emphasized the importance of initiating the process and swiftly transitioning from an initial version to a more refined one. By the end of the session, attendees had successfully completed their gap analyses. In fact, by the final slide of the presentation, many participants were already taking steps to address and rectify the identified gaps in their food fraud prevention measures. Notably, one of the packaging suppliers, which was not directly involved in food production but supplied packaging to the food industry, initiated updates shortly after the seminar.

Key Takeaways

Non-food suppliers to the food industry must implement food fraud prevention systems, as many are not yet compliant. Food companies are increasingly demanding transparency and stringent evaluations of food fraud prevention compliance throughout the supply chain.

Rather than waiting for an audit non-conformity or a recall, take these simple first steps:

1. Identify the food safety management system requirements for your customers.

2. Conduct a Food Fraud Gap Analysis.

3. Perform a Food Fraud Initial Screening (FFIS) activity.

About the author:

Dr. John W. Spink, an Assistant Professor at Michigan State University’s Eli Broad College of Business, is a renowned expert in food fraud prevention. He serves as the Director of the Food Fraud Prevention Think Tank and is the Lead Instructor of the Food Fraud Prevention Academy, offering free online training. Dr. Spink’s extensive research spans policy development, strategic insights, and procurement best practices to safeguard supply chains from disruptions caused by food fraud. Notably, he authored the seminal textbook “Food Fraud Prevention – Development, Management, and Implementation” in 2019.

-

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

FeaturedRisk management

The Cost of a Breach: What a Cyberattack Could Mean for Food Safety Recalls

-

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

FeaturedRisk management

Securing the Food Chain: How ISO/IEC 27001 Strengthens Cybersecurity

-

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

FeaturedRisk management

Revolutionizing Food Safety Training: Breaking Out of the “Check-the-Box” Mentality

-

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

GFSI Standards

GFSI 2025: Building Trust, Tech-Forward Solutions, and Global Unity in Food Safety

-

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

FeaturedFood Safety

Integrated Pest Management: Strategies to Protect Your Brand’s Reputation

-

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants

FeaturedFood Safety Culture & Training

No Open Door Policy: Challenges That Impact Pest Control in Food Processing Plants